Solar eclipse maps from 1891 to 1900

An important and interesting writer who popularized the appreciation of solar eclipses during this era was Mabel Loomis Todd, also famous as an editor of Emily Dickinson’s poetry that was discovered posthumously. Her husband was David Peck Todd, professor of astronomy at Amherst College in Massachusetts, author of books on astronomy, and leader of a number of expeditions to observe solar eclipses and a transit of Venus.

Mabel Loomis Todd wrote three books that pertain to solar eclipses and are worth reading today.

Total Solar Eclipses of the Sun, published in 1896, was a popular and well-illustrated guide for the general public and can be found at http://www.archive.org/details/totaleclipsessu00toddgoog.

Corona and Coronet, published in 1898, is an account of the Amherst College expedition to Japan for the eclipse of 1896 August 9 and can be found at http://www.archive.org/details/coronacoronetbei00toddiala.

Tripoli the Mysterious, published in 1912, is an account of two eclipse expeditions to Libya for the eclipses of 1900 May 28 and 1905 August 30. This book can be found at http://www.archive.org/details/tripolimysterio00toddgoog.

Mabel Loomis Todd and David Peck Todd were both colorful characters and two asteroids are named after each of them.

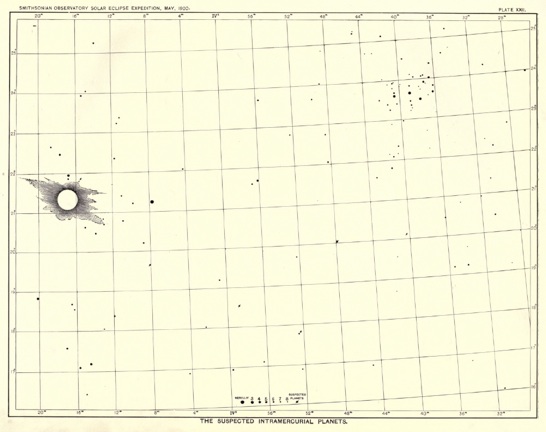

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a subject of intense scrutiny was the search for new planets within the orbit of Mercury. Total solar eclipses were of course an ideal opportunity to investigate this possibility.

An intramercurial planet was hypothesized by Francois Arago, directory of the Paris Observatory, because of anamolies in the orbit of Mercury (which were later explained by Einstein’s theory of relativity). This purported planet was named Vulcan and was the subject of searches during several solar eclipses. During the eclipse of 1878 July 29, two trained observers claimed to have seen Vulcan near the sun.

When you examine the U.S. Naval Observatory eclipse supplements of the time, you can find several maps like this which were used by astronomers to search for Vulcan. After a number of attempts, Vulcan was never confirmed to exist.

Sources

The maps from the British Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris were found and extracted from http://books.google.com.

The maps from the French almanac Connaissance des Temps are from the collection of Michael Zeiler or were found and extracted from http://books.google.com.

The maps from the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac from 1891 to 1900 are scanned from the collection of Michael Zeiler

The 1894 maps of global tracks of eclipses from Mabel Loomis Todd’s Total Eclipses of the Sun are from http://www.archive.org/details/totaleclipsessu00toddgoog.

The 1896 map of an eclipse in Japan is from Corona and Coronet, found at http://www.archive.org/details/coronacoronetbei00toddiala

The newspaper pages for eclipses were found at U.S. Library of Congress page on Chronicling America: Historican American Newspapers, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Sheridan Williams provided several eclipse maps for 1896, 1898 and 1900 eclipses from Judd & Co. and Wyman. I believe these are from the eclipse supplements to the British Nautical Almanac, but this needs to be confirmed.

The map of the 1900 May 28 eclipse by Camille Flammarion is from Astronomy for Amateurs, found at http://www.archive.org/details/astronomyforamat00flamrich

The map of the 1900 May 28 eclipse by David Todd is from New Astronomy, found at http://www.archive.org/details/newastronomy00todduoft

The map of the 1900 May 29 eclipse by Simon Newcomb is from McClure’s Magazine, May 1900, collection of Michael Zeiler

1900 maps from the Appleton’s Popular Science Monthly are from http://books.google.com.